Portrait of the artist as an explorer

by Bernard Goy

If one had to provide an answer to what is at stake in the diversity of art of the XXI century by pointing out a main trend, that trend would be, without a doubt, diversity itself.

While modern art favored novelty and emancipation from the codes of representation inherited from tradition, the so-called contemporary art has forsaken the appearance of art itself so as to

question its meaning. Perhaps today’s artists no longer have any formal boundaries to cross or any cultural constraints to overtake; perhaps they are rather attempting to rephrase meaning in a

wide open global space where everything seems possible.

In this matter, the work of Philippe Guérin represents very well the quests of our times, which are constantly opening new paths and in which all techniques and all genres cross.

Philippe Guérin chose painting. However, to him this choice must remain open. Since the end of the 80s, he has explored its many possibilities, whilst remaining loyal to Georges Braque’s command,

“Never adhere”.

Hence, no line of conduct and no school of thought. Rules, yes, since no meaning can exist without them, but no identifiable periods in this work. However a style asserts itself, or rather stands

out. Indeed, no more than the painter’s personality, does his art assert itself. One rather feels that the painting reveals itself, through a brilliant mixture of profusion and restraint, of

formal richness and iconography combined with a rigorous economy of gesture.

The explorers of past centuries were also, more often than not, fierce conquerors, if not actual brutes, whose victories were littered with bloodsheds, or at least many damages. Following the

example of today’s explorers, who tread carefully through the natural environments and the societies they encounter - through alterity - Philippe Guérin pursues a quest in the manifold space of

painting, in which discoveries resonate like tributes to its history and its languages.

Whilst resisting the quotational fashion to which contemporary art is subjected, his work overflows chronological and conceptual systems, following the inspiration of the moment. Thus, the

painter can conjure up modernist Abstraction to structure the scansion of a great epic painting like the sumptuous red polyptych. He can also summon, in a desire for landscape - be it calm or

even melancholic - the styles which preceded Abstraction, and join the aesthetic family of Léon Spillaert or Odilon Redon, who were themselves the silent pioneers of modern art.

Often similar to the sign, the gesture can also steer away from it to explore the classic grandeur of painting, that of the XVII century - the century of Rembrandt, of Philippe de Champaigne -

and then, through a mere shape, it can bring to mind the work of Goya.

This freedom is a choice in itself.

And if the work doubtlessly contains tributes, they are not definite, but seem to emerge whenever the artist looks for a form through which to express a feeling or testify of a contemporary

situation.

There is perhaps most clearly highlighted the fact that this work belongs to contemporary art: certain trends of modern art yearned for the “tabula rasa”, the empty slate freed from traditional

heritage, so as to start anew and look only towards the future.

History showed that this was an ingenuous and guilty ideological mistake. Today, art history shows that the “contemporary age” which the French art critic Paul Ardenne describes in a book, has

sized up this ingenuousness, although up to and including the 50s many masterpieces were created with the energy of discovery. However, towards the end of the 80s, this beautiful energy

transmuted to doctrine and dwindled.

The echo of the body

“Today the body is the primary given fact”, wrote François Pluchart at the end of the 60s. Nowadays, at the dawn of new global transformations, the body is problematic. Contemporary art already

takes into account this new given fact. Video, photography, sculpture, all translate the recent situation in which it is no longer a hostile nature which threatens man’s biological integrity, but

new technologies - those which tomorrow will be able to alter this “primary given fact”.

Throughout the past centuries, Western painting was the means through which human form - “the only form that mattered”, according to Goethe - was revealed.

The representation of the body is a major part of Philippe Guérin’s painting. The diversity of approaches which the painter brings to this central aspect also represent the diversity of our

points of view today, after Cubism and all the formal diffractions which characterize our times. Whether it is placed in a majestic situation or threatened by obliteration, the human body always

seems to rise to the surface. There, fallen or suffering, here, soothed, it shows itself through the well known mode of remanence, like a forgotten thought, held back by the past but suddenly

appearing in another painting. The exploration of the pictorial space to which the painter commits himself, seems to lead him inevitably towards the only form that is worthwhile, but only in the

manner of the fugue, a half-revealed form, which disappears and then returns, like a memory of humanity which would refuse amnesia.

Through this relentless quest which takes on the confused contemporary condition, the painting of Philippe Guérin is without a doubt, very close to the reflection of the French philosopher

Bernard Stiegler who explained the role of art through these words, published in an interview for L’OEIL magazine a few weeks ago:

“The role of art? Creating judgment.”

Bernard Goy, April 2011

Translation: Catalina Onofrei

Exhibition catalogue - Painting : Alive ! - 2011, Sichuan Museum, China

Philippe Guérin : the canvas of life

by Olivia Sand

Writing about Philippe Guérin’s work is a very challenging undertaking as over the years, he has continuously been reinventing himself. There is not one “style” that makes his work immediately

recognizable, but much more a handwriting that has been fundamental in exploring different horizons. Over the past decades, we have witnessed many artists who were extremely gifted at telling

stories, but over the course of their career, the stories remained more or less the same. Philippe Guérin on the contrary, tells us diverse and beautiful stories which on the canvas materialize

in very distinct forms in order to build the canvas of life. If one were to summarize his work on a more general level, it would appear very clearly that his main “oeuvre” is to tell the story of

painting, and Philippe Guérin shows magnificent talent for that.

For as far as we can look back, Western painting has predominantly been anchored in the representation of the human figure. Philippe Guérin (born in 1952 in Chalon sur Sâone, France) has always

expressed a strong attachment to some of the great schools and masters of the past centuries (whose expertise has in some cases never been surpassed), and acknowledged their legacy. He belongs to

the great advocates of figurative painting with the constant concern to somehow integrate the legacy of these early masters in a more contemporary way. Even in a time not too long ago, when the

art world voiced loudly that painting was “dead” and that everything had been said, Philippe Guérin never lost sight of the fabulous tool that painting represented, and all the possibilities it

had to offer. He never turned his back on the medium, even as it was commercially speaking more interesting to venture towards other media like photography, installation or video.

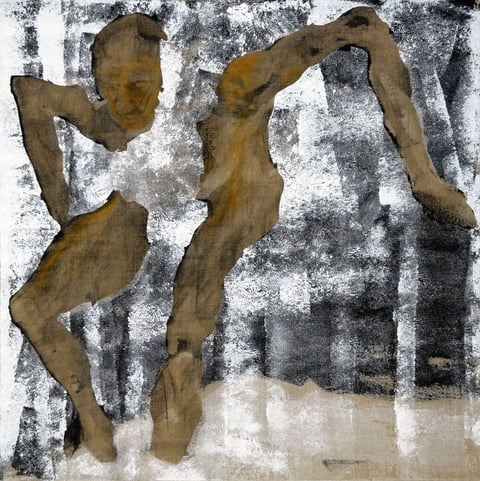

An impressive draftsman, Philippe Guérins’ skills beautifully come to the forefront when depicting the human figure. Equally at ease with pencil or with brush and color, he takes great care not

to reveal the entire figure with all its features : he emphasizes considerable detail on certain parts (a torso, a silhouette...), juxtaposing them with other segments of the canvas that are

painted in a looser fashion. In that sense, he marvelously entertains a certain mystery as to the identity, the setting or the context of his works, thus allowing the viewer to become a

protagonist by inserting the missing pieces.

What transpires throughout Philippe Guérin’s body of work shown in this exhibition is that his pieces have weight, are firmly grounded, and above all have meaning. They convey life with all its

journeys, and therefore, they call for reflection. Each of us may find their own truth in these pieces which are drastically authentic. And this after all, remains and will remain an experience

that for any viewer leads in a certain way to introspection and assessment. This reinforces our belief that painting is well alive, and what better example to prove it than Philippe Guérin’s

“canvas of life”?

Olivia Sand, March 2011

Exhibition catalogue - Painting : Alive ! - 2011, Sichuan Museum, China

Sébastien Prévoteau

Born in Chalon-sur-Saône in 1952, trained as an architect, Philippe Guérin decides on Painting after his graduation. Close to a classical tradition of body representation, he uses various color

modalities with which he establishes geometrical combinations and experiments numerous techniques, using covers, stencils, and adhesive tapes. The mannerism of the figures, whose power and motion

sometimes evokes Michelanglo, answers a rather abstract pictorial treatment, extending from broad tint areas to paint spurts reminiscent of Jackson Pollock. Faced with the classical opposition

between figuration and abstraction, he chooses cohabitation, and substitutes the “one or the other” alternative for a “one and the other” dialectic. This plastic cohabitation - this friction of

the heterogeneous - sometimes seems to submit bodies to the paroxysmal tension of a dull and restrained convulsion. It is being galvanized by the knitting of a third element which provides

cohesion to the plan. Defined as an empty space, a passing or a reservoir containing “available energy”, it bestows on the whole work a dramatic dimension, an ontological dimension (and not only

technical) by the very emergence of the figure, appearing in its place and in its space. Here, “their heads are heavy with dreams”, a woman faces this character, hardly sketched, viewed from the

back, which seems to occupy this empty space, vacant and interchangeable, maybe even intermediary of the pictorial site ; painter or spectator, witness or voyeur ? Today, “leaving some emptiness

may be a way of evicting conflict”, or else the figure, here shaped, modeled or skirted would probably not happen.

Sébastien Prévoteau

http://collection.centrepompidou.fr/specificData/standard/notices/nra/D020955.htm#

Philippe Guérin

by Bernard Goy

The first word that comes to mind at the sight of the recent paintings by Philippe Guérin is elegance. This word (which approximates another, spirituality) has the advantage of lightness. Not of

that style of mannerism which empties the work of what is at stake in it, but rather, in this case, an attitude of considerable tact towards painting and representation, a sensible standing back

to allow the incarnation of the subject to stand forth in its own time.

The second word would perhaps be quality. A hollow term I admit as served up with just about everything that goes in contemporary art. All the same, it retains a certain resonance before these

tableaux whence emanate an attention to what is treated which is never a control of a detail but rather a sort of harmony between painted surfaces, lines and reserve that the image leaves

uncaptured. Hence the reserve is a passageway, an invitation to depart from the real space where the painting is hung to enter the figured space it opens.

Whereupon appear other stakes, those of a meaning which remain or have become once again in recent times the sole reason to paint and look at paintings. Philippe Guérin recognizes in the work

itself, his own, an ethical (but not didactic) dimension of witch painting would be in some sense be but the laboratory.

Quite to the contrary of that of Gehrart Richter, the distance maintained by Philippe Guérin is always put to the test of the subject. A tidal wave of pink whose explosion threatens the integrity

of three rounds forms who are its immobile witness, answer to the glory of a cruciform whose abandoned form resolves all conflict. To the impetuous expanse of one form answers back the luminous

withdrawal of another. Elsewhere, the same hue of blue flutters in a flower or in a butterfly as in the eyes of a little girl. Somewhere else again the tenuous apparition of a woman’s face seems

to be looking at us through the weave of the canvas. What is happening on these surfaces also plumbs the depths of a life.

Interview

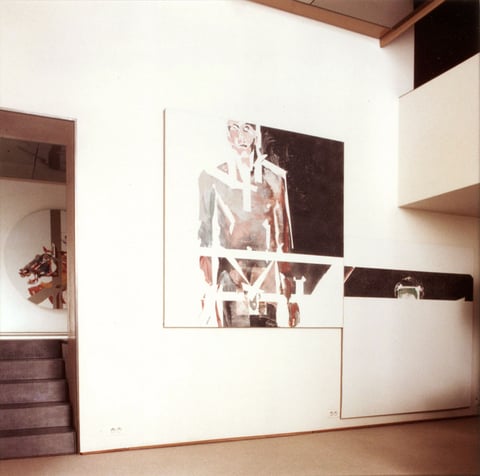

An old painting by Philippe Guérin bears the title Their heads were heavy with dreams. It presents a couple. The woman, seen in three quarter profile, is fully

painted in while the man, seen in three quarter back, is but half painted a large part of his figure being occupied by the reserve (the unpainted surface). Our conversation on the subject of his

recent paintings began with this theme. In addition, certain somewhat geometric, abstract elements collude in upsetting the sight of the figured subject and its space.

Philippe Guérin : Still today I like to strike a balance between the presence of the surface and that of the subject inscribed upon it. Not “one or the other” but “the one and the other” as a

friend of mine puts it. These elements, those of surface and abstraction, were for me a grammar, the means for learning how to paint.

Bernard Goy : A modern apprenticeship?

P.G. : Upon discovering Mondrian abandoned the idea of painting pictures and instead chose to study architecture. I only began to paint in earnest in 1974.

B.G. : 1974, “Support surfaces” ?

P.G. : In painting I have never adopted a political posture, but “Support surface” did interest me. My paintings have always tried to say, “I am a canvas stretched out upon a stretcher”.

B.G. : One senses that you recycle elements which once had a value all unto themselves in modern art, a little like “reemployment” in architecture when already used materiel is used again to

construct else.

P.G. : I use them to make them into a work, I take elements which one had a theoretical value to make a painting.

B.G. : You don’t imitate the textures of reality, but you do imitate the model.

P.G. : You are right, I attempt to be lifelike, to be true to life. Ultimately, if anything is true, it’s not the face, it’s the light on the face, the light of the moment.

B.G. : From Cezanne to Rauschenberg there has been a long history of the use of the reserve; do you have the feeling that, by using it so extensively, (you are rather self-taught) and an

historical emptiness (today there is no longer an historical model of representation that one could imitate) ?

P.G. / I all the same received academic training in drawing from a teacher who was quite gifted. He could do paintings in the Cubist, Surrealist, Fauvist and impressionist styles… I was 17

at the time. The training period was short, one year I believe, but it has its importance. As for Cezanne… Well, I lived in Valence at that time. People spoke to me quite a lot about him. In his

Sainte-Victoire the reserve is for me a breath of fresh air. In that little elephant in profile, if one looks closely, there are little virgin surfaces which could well evoke a face, or a full

frontal view of a black African mask. It’s perhaps that which opens the space. I still like the idea that one can enter or leave a picture. In Manet, the entrance becomes lateral and no longer

perspectival. When one paints one can enter one side and then one must leave. But listening to you, the use of the reserve perhaps also comes from the words of that professor who said : “When one

doesn’t know how to paint, one doesn’t paint with oils!” (smiles).

Finally, the reserve, the void, is an available energy. Leaving some emptiness is perhaps to eliminate conflict. I would cover the whole canvas if light could be everywhere.

Which is true of one of Philippe Guérin’s latest paintings. Even though the canvas is not completely filled in, light circulates upon it with the felicity of a fine Florentine afternoon when the

shadows of the architecture and luminous reflections upon the bodies balance one other.

Bernard Goy, 1996

Translation: Christopher Bennett

Exhibition catalogue -Menus objets du désir de peindre - 1996, Art & Patrimoine Gallery, Paris, France

Philippe Guérin

by Marc Hérissé

Trained as an architect, this artist of 41 is able to perfectly structure and compose a canvas but he also has the sensitivity to make one not notice it. To speak of his works is difficult for they are at once brutal yet refined, figurative yet forgetful of figuration, austere yet rich. Near a large, exuberantly free canvas entitled I’m watching, harmoniously blending, as though by means of a crucible, acrylics and crayon, oils and charcoal, lead and asphalt, the artist presents eight small formats whose stapled canvas slightly exceed their stretchers and which are so many autoportraits. But autoportraits seen, by a subtle play of mirrors, through the eyes of someone else and presented as foreshortened figures, like the head of the Dead Christ by Mantegna at the Brera in Milan. Using shades of black, grey and earth, these analogous works vary subtly to pay homage to Van Gogh, Tolstoy, etc. In a nearby room, an abstract painting, Tender devastation, fascinates with its carnal cinetism.

Marc Hérissé, 1993

Translation by Christopher Bennett

La Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot, n° 33, page 69

Exhibition Tête à têtes, 1993, Art et Patrimoine Gallery, Paris, France

Philippe Guérin – Unifor Space

by Anne Dagbert

The exposition of this young artist in a luxury furniture loft could be called “Promenade in an androgynous country”. Androgynous in a double sense, first from the perspective it takes on painting and architecture as exemplified by the way the works are sequenced and juxtaposed. Androgynous above all by the spirit of the paintings and the way they represent the body in an undetermined and aver so seductive state somewhere between masculine e and feminine. Architect by formation, Philippe Guérin has conceived a sequencing of his works, a light-hearted saunter among the home and office furnishing by the Italian designers Tobia and Afra Scarpa that, if it brings out no explicit relationship between the artistic and the utilitarian, nevertheless has its attractions. The refined, light-hearted aspect of the painting, their tender colours, the decorative character of the small, landscape simulating crosses arrayed upon the paintings, the elegance de the large black and white tracing paper panels profiling undecided, anthropomorphic lines, all this tempers the rigidity of the furnishing. A tondo in particular drew my attention because of the way, with considerable brio, the images of a woman, a man and a horse intersect one another to form a dramatic X. on the painting treated in grisaille in front of it, a human figure sways troublesomely in the exaltation of an androgynous desire.

Anne Dagbert, 1987

Translation: Christopher Bennett

Art press, n°116, page 36

Exhibition Unifor Space, 1987, Paris, France

Philippe Guérin in Saint Maur Museum

by Jean François Mozziconacci

Philippe Guérin was born in 1952 in Chalon-sur-Saône. At the same time he's being schooling, he studies drawing. While going to school, he begins to study drawing. In 1976, he graduated in

architecture with a thesis entitled “architecture and dream” which allowed him to study certain links between this subject and painting. He has devoted his time to painting ever since. He

exhibited in Rome in 1979 and 1981 and in Paris in 1982. His architectural background is visible in the rigour he uses to balance his compositions and to organise links between colours. Hints to

a classical tradition are numerous, such as power and motion of bodies, or rhythm and perspective of figures inside groups evoking Micheangelo (drawing 13) or Tiepolo (canvas 3). This tradition

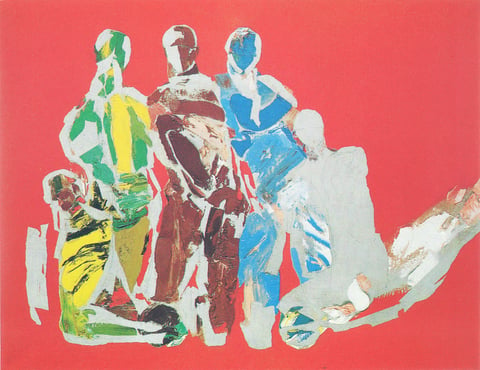

is completed by an admiration for American abstraction which is visible in the use of firmly modern techniques, in particular with the use of industrial paint (Canvas 1 and 2). Legacy and trends

are integrated and exceeded by a solid personality, as in the canvas 4 which evokes American hockey players with their mannerist powerful muscles and the treatment by paint spurt reminiscent of

Jackson Pollock. His confidence and mastery are asserting themselves in the play between flat backgrounds and blank figures, between the balance of characters and the dynamism of composition,

emphasised by the use of the brush or the knife, at last with the colour: quietness of cold tints (canvas 10), warm transparencies for the couples of the polyptych (canvas 5 to 8) or violence of

the figuration of torn bodies on a red background, desperately uniform (canvas 14).

Jean François Mozziconacci, 1983

Exhibition catalogue - Philippe Guérin - 1983, Saint Maur Museum, France